What to do when the media gets it wrong

You carefully craft a press release. You go through rounds of internal edits and approvals. The quote is massaged more than LeBron James’ ego. You send it out to the media… and the published story has errors.

Sigh.

Unfortunately, this scenario is becoming all too common. In today’s web-driven, social media-centric news landscape, some journalists can prioritize being first more than being accurate. The reality is that reporters are forced to do more with less and crank out stories faster than ever before.

At the same time, misinformation now spreads faster than measles at an anti-vaxxers convention. And, once people are exposed to misinformation, it’s incredibly difficult to remove its influence. As the saying goes, mud sticks. So what can you do if the media gets your facts wrong?

To err is human, to correct divine

If a media outlet has published something with factual errors, the first step is always to contact the reporter and ask for a correction. Nearly all journalists worthy of that title want their stories to be accurate and will welcome the chance to get it right. The key is to remain focused on the facts — not the angle, tone or way the story was written.

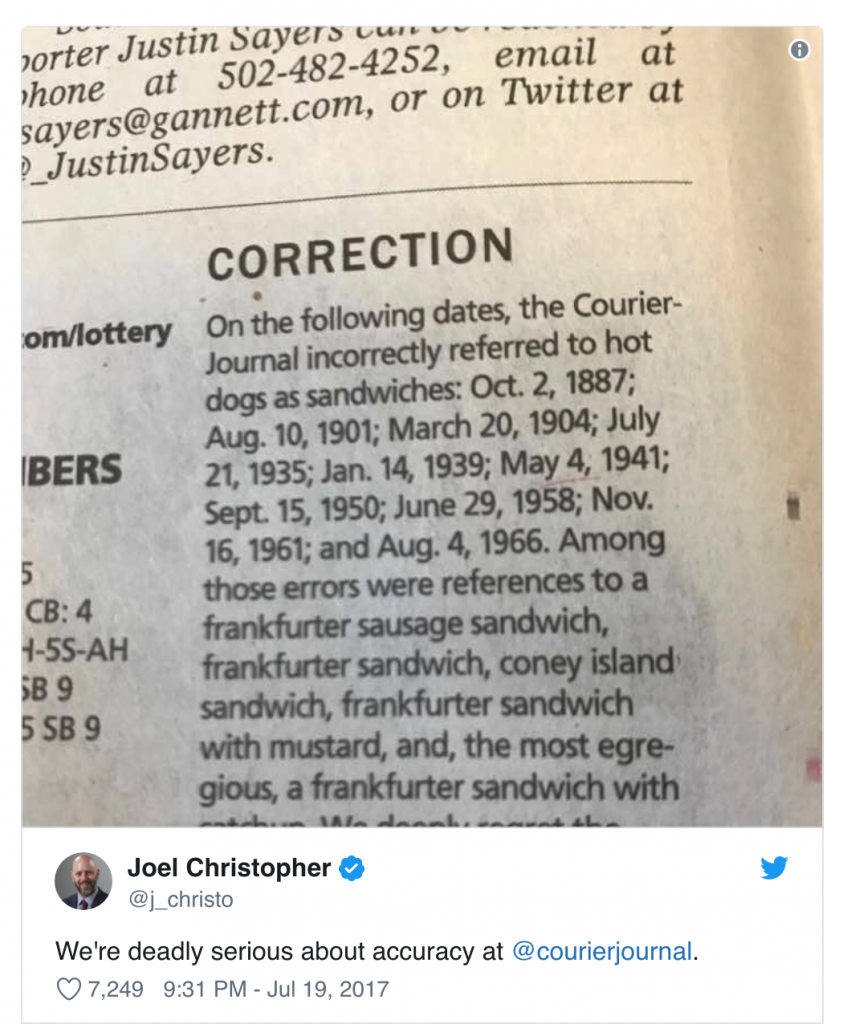

If a reporter is unresponsive or resistant to correct a factual error, speak to an editor, producer or news director. However, weigh the importance of your relationship with the individual reporter with getting the facts straight. If it’s a minor error like a misspelling or incorrect date, you may want to let it go to preserve your relationship. As the saying goes (from back in the analog days), “Don’t make an enemy of someone who buys ink in a 1,000-gallon drum.”

A heavy-handed approach is never a good idea, no matter how frustrated you are. Keep in mind that the mistake may not have been the reporter’s fault — headlines, for example, are rarely written by reporters, and an editor may have inadvertently made an error during the editing process.

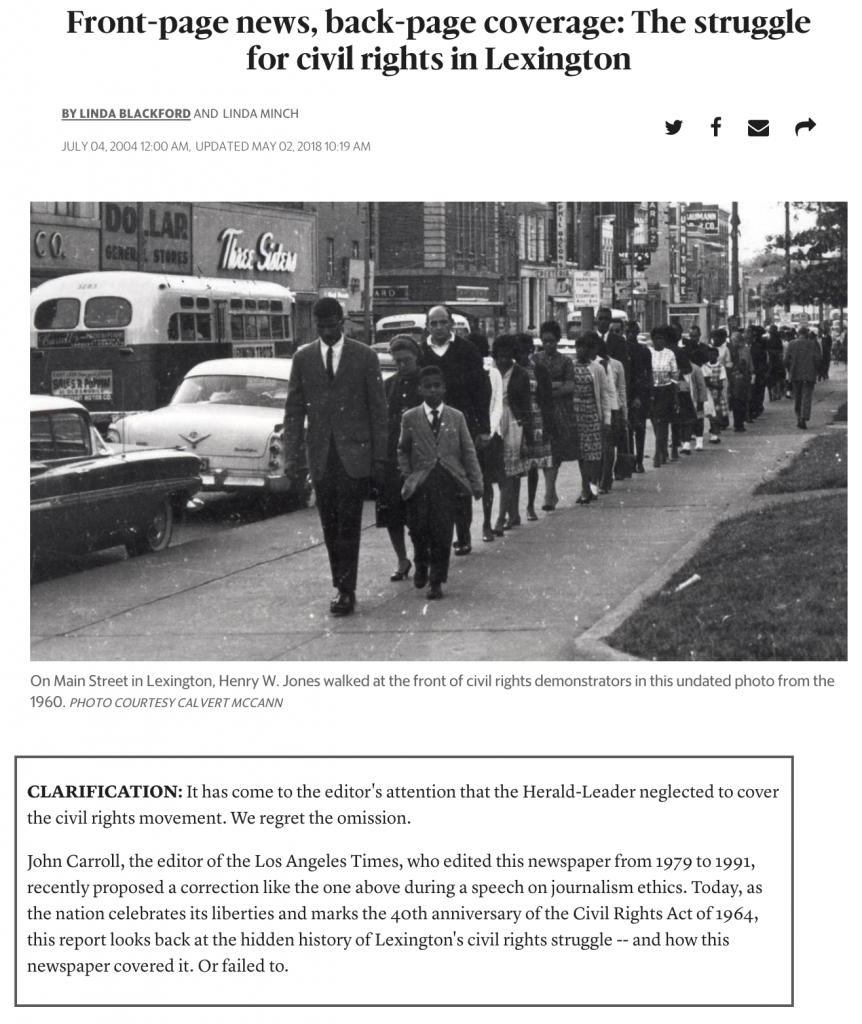

Note that I said to ask for a correction — not a retraction. A retraction is a request for the media outlet to fully remove the article (if it’s online only) and admit it got the entire story wrong. Retractions are incredibly rare, whereas corrections are commonplace.

Other errors: omissions and context

Factual errors are straightforward — most journalists want to get it right. But what happens if a reporter doesn’t tell the whole story, and the omission or lack of context impacts understanding?

This is where relationships help. If you know the reporter and have been a valuable resource in the past, it’s much easier to have a conversation and explain your perspective. Here, it’s important to remember that the reporter is not your PR professional. They are not in the business of writing stories to please sources. However, a reporter might be open to a polite, constructive conversation about the wider issues that they may have missed in their reporting.

Tread carefully, and remember that you cannot guarantee an outcome. If the reporter declines a correction, then your options are to write a letter to the editor or post content on your own platforms, including a blog or social media. You can then comment on the original media story with a link to your blog post. Your own post might also steal some SEO juice from the news story, and bring people to your website for your side of things.

If you choose to address misinformation via your own channels, be careful not to repeat the inaccurate details unnecessarily. Even though you are showing why a story is false, the very act of repeating it can entrench the misinformation in your audience’s mind. Instead, focus on the facts. The goal is to increase familiarity with the right version instead of the incorrect information.

Mud sticks: preventing misinformation and errors

What’s better than getting a correction? Not needing one in the first place.

While minor errors are regrettable, those that fundamentally change how clients, stakeholders and others perceive you or your company are a much bigger problem. The longer people are exposed to misinformation, the more likely they are to believe it — regardless of whether it is proven false. Thus, it’s important to quickly debunk misperceptions and even more important to prevent them in the first place.

Here are a few tips:

1) Respond via email

If you are asked to comment on a highly sensitive matter or complex subject, often it’s best to correspond with a reporter over email rather than agreeing to a phone conversation. Simply let the reporter know that you would like to respond but you’re unavailable for a phone call and can provide a quote via email. Ask the reporter for the story angle, the questions to be answered and the story deadline, then quickly write and send your responses.

2) The more you say, the more you stray (so keep it brief)

If you are speaking to a reporter in person or over the phone, develop key messages in advance and stick to them as best as possible. Be brief and don’t ramble — newspaper quotes typically are 10 to 25 words, and broadcast soundbites are 15 seconds or less.

Remember that a reporter likely has multiple stories to file. Their goal is to get the quotes they want, not an in-depth dissertation on the subject.

3) Ask to review quotes

While it’s never a good idea to ask a reporter to review their story before it’s published, it’s OK to ask to review direct quotes for factual accuracy.

In addition, if you’re speaking about complex or sensitive subject matter, you may want to ask the reporter during the interview to repeat what you’ve just said. Be careful not to sound condescending and instead convey a desire to help the reporter understand the material.

4) Provide written background information

Prepare a fact sheet in advance of the interview and send it to the reporter. Or, write a blog post on the topic and point the reporter to it.

5) Ask the reporter several questions in advance

Before committing to an interview, ask the reporter:

- What the story angle is (“What’s your take on the subject so far?”)

- Who else is being interviewed

- What they would like to cover with you

- The reporter’s deadline

6) Understand a reporter’s job and prepare accordingly

For example, TV reporters are often trying to elicit emotion and will ask questions designed to get emotionally laden responses.

7) Use “off the record” wisely

If you choose to speak off the record, understand how it works. (Here’s a good primer.)

(Self-serving tip alert)

Hire a good PR pro, who will take care of all of this for you and prep you for the interview. They can also assist with securing corrections, if needed. You’re busy. Why sweat these details?

Have you been misquoted or felt like the media misconstrued the facts? How did you handle it? I’d love to hear more tips. Email me at michelle@rep-ink.com or comment below.